A small number of tuberculosis cases have been detected among migrants at city shelters, the Chicago Department of Public Health confirmed.

The health department could not share exactly how many cases were found or identify shelters. But the department said there haven’t been any reports of TB in the city from an exposure to migrants positive for the infection.

TB cases pop up in Chicago each year, with about 100-150 infections detected annually, said Jacob Martin, a spokesperson for the health department. Because of that, the health department needs to sort through its data to figure out which cases are new arrivals and which are other city residents. Those numbers will be made public once that analysis is complete.

“I would not characterize this as an outbreak,” Martin said. “It’s relatively inline with what we expect to see.”

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly Chicago Catch-Up newsletter here.

These cases aren’t the same as the recent measles outbreak because TB occurs in Chicago each year unlike measles, said Dr. Emily Landon, an infectious disease doctor at University of Chicago Medicine and the hospital’s executive medical director of infection prevention and control.

TB is curable with antibiotics, and transmitting the infection to others typically requires hours of contact between individuals. A person can also be infected with TB, but the infection remains dormant in the body for years, similar to how chickenpox can linger throughout someone’s life and then eventually pop up as shingles, Landon said.

About 10% to 20% of Central and South American residents have latent TB infections, Martin said, meaning they’re positive for the infection but are asymptomatic and can’t pass it to others. But he said the health department is still working out which of the recent cases are latent and which are active infections.

When migrants receive care from Cook County Health, they’re screened for TB, among other illnesses, Martin said. The department also prioritizes getting people vaccinated against a range of communicable diseases.

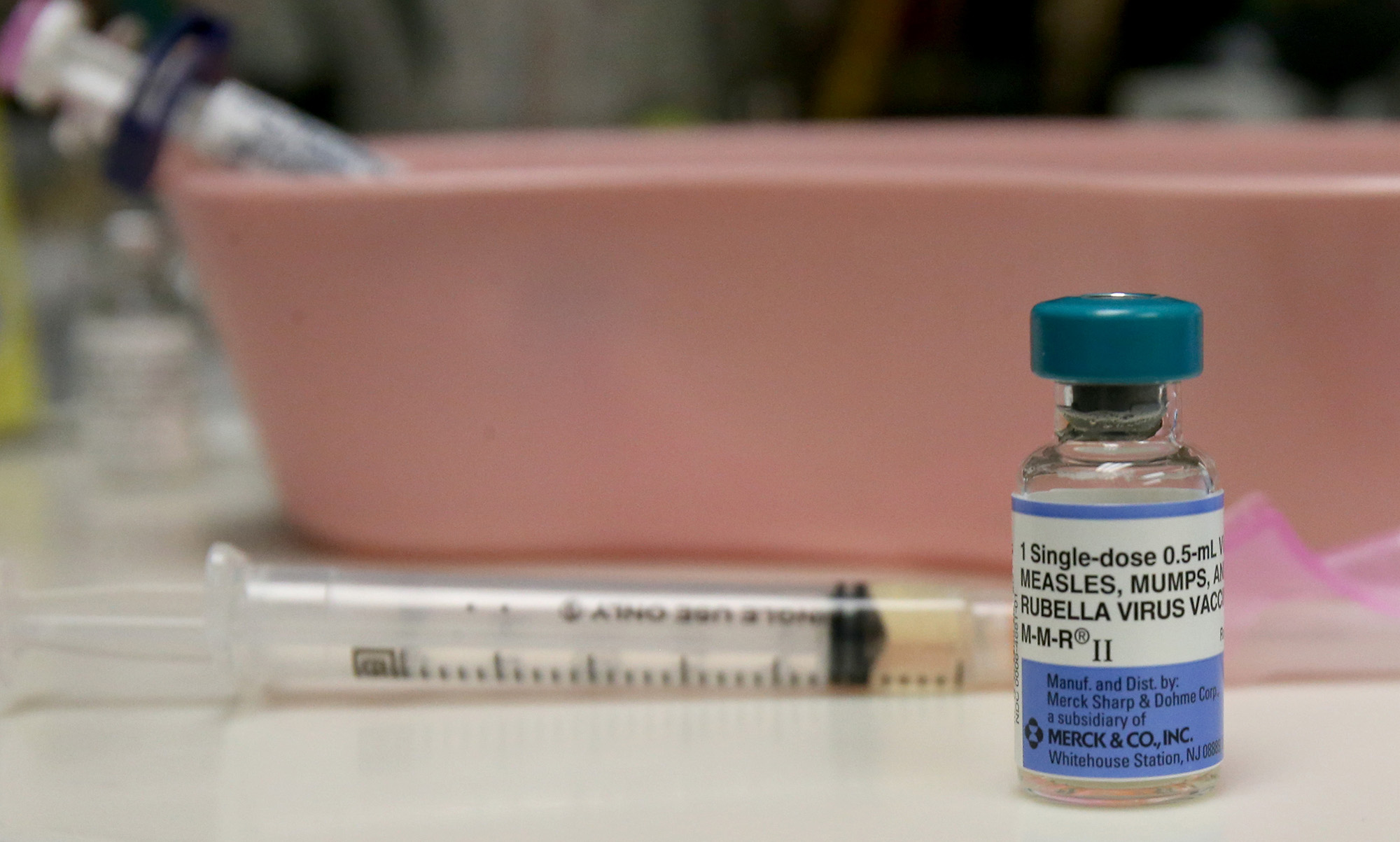

“We are literally always pushing to get more people vaccinated. With these vaccine-preventable diseases, we can prevent their spread with vaccines,” Martin said.

Those vaccines include COVID-19, flu, chickenpox and measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR). Just in the last month following the measles outbreak, the department has administered about 6,000 MMR vaccines to migrants, Martin said.

For patients with an active TB infection, the health department assigns a nurse case manager to each person and conducts contact tracing.

Symptoms can include a bad cough that lasts three weeks or longer, pain in the chest and coughing up blood, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Patients with TB can also experience fatigue, weight loss, lack of appetite, chills, fever and sweating at night.

Anyone with latent TB can receive a treatment that nearly completely prevents the disease from being reactivated, Landon said.

The worry is with children ages 5 and younger contracting TB, she said. And these cases are likely popping up more often in children than adults because some Venezuelan children are only partially vaccinated or not vaccinated at all.

An Associated Press analysis found that Venezuela’s vaccination rate is among the lowest in the world. Experts largely blame the ongoing political turmoil and the unraveling of the country’s health system.

Many Venezuelan children, for example, lack several of the 10 vaccines recommended by 12 months of age to protect against 14 diseases, including polio, measles and tuberculosis, the AP found.

“We don’t need to be afraid from an infectious diseases standpoint; the city’s doing a great job of managing the infection risk,” Landon said. “And all the doctors in the city, especially the infectious disease specialists, are working really hard to have great pathways for new arrivals that bring in diseases that we already know about.”

These cases and other outbreaks are not a reason to be afraid of migrants, she added. Rather, it demonstrates the health risks they might face coming to the city.

Public health issues have been plaguing migrants for months, especially those staying in city shelters. At least 52 cases of measles have been confirmed in Chicago, and most are from an early March outbreak at the crowded migrant shelter in Pilsen. This was the first time measles was detected in Chicago since 2019.

About two-thirds of the confirmed cases have been in children 4 years or younger, while about a third were in adults 18 to 49 years old, according to the city.

The Pilsen shelter is the same facility where a 5-year-old boy died in December from sepsis and a bacterial infection that causes strep throat, according to an autopsy. Contributing factors to his death were listed as COVID-19, adenovirus and rhinovirus.

Other children staying at the shelter were also hospitalized at the time amid complaints of unsanitary and overcrowded conditions.