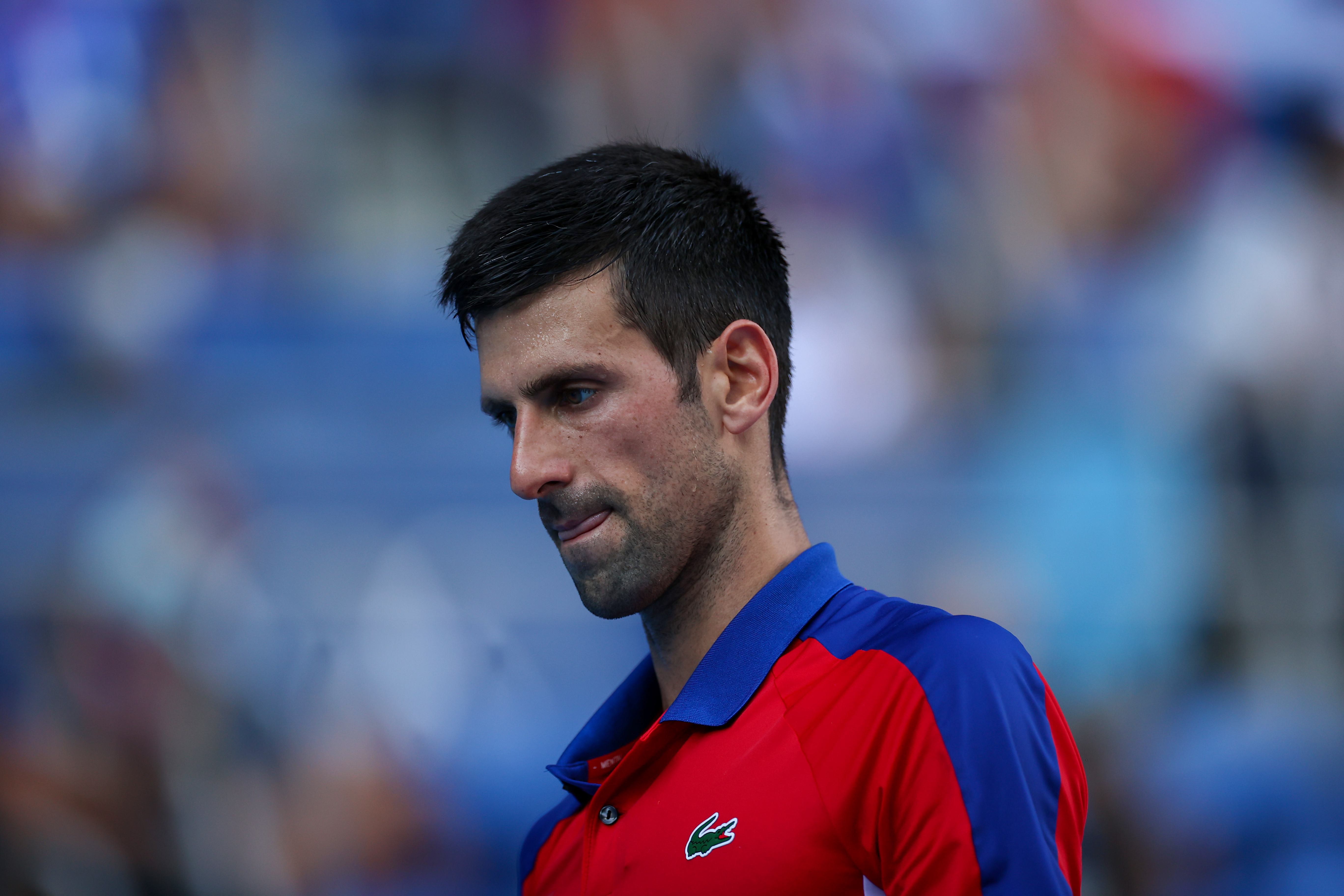

Novak Djokovic won his first legal round against Australian authorities who want to deport him. But the world tennis No. 1 now faces a formidable challenge on Sunday in his second round as he takes on what some describe as the God-like powers of the immigration minister on questions of visas and public interest.

Djokovic won his court appeal this week against a border official’s decision to cancel his visa. He won over procedural errors related to Australia’s confusing COVID-19 vaccination regulations.

Immigration Minister Alex Hawke’s intervention on Friday to cancel the visa a second time for what Djokovic’s lawyers describe as “radically different” reasons pits Djokovic against Australian politics and the law.

WHAT ARE THE MINISTER’S POWERS?

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly Chicago Catch-Up newsletter here.

Hawke has a “personal power” to cancel Djokovic’s visa under Section 133C of the Migration Act 1958.

Hawke needed to be satisfied that Djokovic’s presence in Australia “maybe, or would or might be, a risk to the health, safety or good order of the Australian community.”

The minister also needed to be satisfied that ordering Djokovic’s deportation would be in the ”public interest,” a term which has no legal definition.

Unlike the decision of a government underling, the “rules of natural justice do not apply” to a minister’s decision. That means the minister did not have to tell Djokovic he was planning to deport him.

More Djokovic Coverage:

Hawke could have canceled Djokovic’s visa in secret and then notified the Serbian tennis star days later that he had to go. Had the Australian Border Force come to detain Djokovic, they would legally have had to reveal only then that he had no visa.

Under Section 133F of the Act, Djokovic could have then requested the minister reverse his decision, but the only realistic option would have been to appeal it in court.

HOW DOES THE MINISTER EXERCISE HIS POWER?

In Djokovic’ s case, Australian government lawyers warned him that the minister was planning to intervene on Monday when a judge reinstated his visa. The star athlete’s high profile might have encouraged the government to appear even handed.

Djokovic’s lawyers provided evidence for why he was entitled to keep his visa and be allowed to defend his Australian Open title in the days before the minister acted.

While Hawke has sweeping discretion to define public interest in canceling a visa, he must also be thoughtful and detailed in his reasoning.

“These decisions aren’t straightforward. There is case law which compels a minister when exercising this power personally to have active intellectual engagement with the materials and with the decision,” immigration lawyer Kian Bone said.

“It’s not something that he (Hawke) can have a one-liner saying: ‘Dear Mr. Djokovic, your visa is canceled.’ He can’t have a bureaucrat or a staffer write a decision for him, look at it for two minutes and sign off on it,” Bone added.

HOW DO YOU OVERTURN A MINISTER’S DECISON?

Because the minister’s power is so broad and discretionary, grounds for appeal are potentially fewer than they are for a decision of a public servant acting on a minister’s authority. But courts have overturned ministers' decisions in the past.

The immigration minister’s powers are among the broadest provided under Australian law, said Greg Barns, a lawyer experienced in visa cases.

“One of the criticisms of this particular power is that it is so broad and it’s effectively allowing the minister to play God with someone’s life,” Barns said.

“It’s inevitable that political considerations would form part of the decision because that concept of public interest is so broad that it allows a minister to effectively take into account political considerations, even though theoretically that ought not be done,” Barnes added.

Political considerations are heightened for Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s conservative coalition with an election due by May at the latest.

Although Australia has one of the highest rates of COVID-19 vaccination in the world, the government is concerned by Djokovic’s popularity among those who are opposed to vaccine mandates or skeptical of the vaccines' efficacy.

Djokovic’s lawyers don’t accept that those sentiments are a legitimate reason to deny the sporting star an attempt at a record 21 Grand Slam titles.

“The minister only considers the potential for exciting anti-vax sentiment in the event that he’s present” at the Australian Open, Djokovic’s lawyer Nick Wood told a court on Friday.

Hawke’s reasons do not take into account the potential impact on those attitudes if Djokovic is forcibly removed, Wood said.

“The minister gives no consideration whatsoever to what effect that may have on anti-vax sentiment and indeed on public order,” Wood said. “That seems patently irrational.”