President Donald Trump clearly supports the oil and gas industry, but he made several false and misleading boasts about his impact on the energy sector.

--The president suggested that a change in federal policy was responsible for a newly operational natural gas export terminal, saying past leaders’ “anti-American energy” policies had led the company to plan an import terminal instead. In fact, the exporting project, and several others like it, were approved by the Obama administration.

--Trump falsely claimed that liquefied natural gas exports were “heading south” before he took office. They increased more than 500 percent in President Barack Obama’s final year in office, as the first major exporting project began operations.

--He said U.S. energy exports “brought down our trade deficit by $215 billion.” That’s wrong. Energy exports have been rising, but the U.S. still imports more than it exports, and the overall trade deficit in goods and services went up by nearly 13 percent in 2018.

Trump spoke in Hackberry, Louisiana, on May 14 at the opening of Sempra Energy’s Cameron LNG project, a liquefied natural gas exporting facility.

LNG Project Approved by Obama Administration

U.S. & World

Cameron LNG is the fourth liquefied natural gas exporting project in the Lower 48 states to begin operations since 2016. All were approved under the Obama administration, after the “shale revolution” took hold, when technologies such as hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling led to increased domestic production. These LNG facilities cool the natural gas into a liquid form and ship it to markets in Asia and Europe.

Sempra Energy announced its plan to create an LNG export terminal in 2012 in a partnership with Japanese companies, and as its website says: “The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission authorized the project in June 2014.”

But Trump claimed a change in federal policy was the reason for Sempra’s facility.

--

Trump, May 14: It was not long ago that Sempra planned to build a natural gas import terminal on this very spot. That was in the past, when our leaders pursued policies that were anti-American energy and anti-American worker and anti-America wealth. It all ended. But those days are over. Now we have an America First energy policy, just like we have an America First policy.

--

We asked the White House press office what “anti-American energy” policies had affected Sempra’s plans to build exporting facilities, and we didn’t get a response.

But the record shows Sempra started its shift from an import terminal, which opened in 2009, to exporting in 2012 and received the appropriate approvals under the Obama administration. Experts told us it takes anywhere from four to six years to build these facilities.

We asked Sempra about the president’s comment, and we received an email response from Kelli Mleczko, corporate communications advisor, who said: “You are correct, Cameron LNG was approved in 2014.”

An April 18, 2012, article in the San Diego Union-Tribune (Sempra is based in San Diego) said the company had announced “development agreements with two Japanese conglomerates to help build a $6 billion liquefied natural gas export terminal at its existing import terminal in Louisiana.” Sempra had formed 20-year agreements with Mitsubishi Corp. and Mitsui & Co. that would grant those companies two-thirds of the export capacity.

“Demand for new export infrastructure is driven by a surge in North American production made possible by new drilling techniques,” the Union-Tribune reported. “U.S. natural gas prices have plummeted to a 10-year low, in stark contrast to prices around the globe.”

Mark Snell, president of Sempra at the time, was quoted as saying, “The attractive thing to us about the structure is our partners will be putting up much of the capital. What we’re contributing is primarily our great location at the site of our Cameron facility and our expertise in project development, permitting and operations.”

Experts told us this was part of a trend of LNG import terminals looking to move to exporting instead, because of the shale revolution.

Eric Smith, associate director of the Tulane Energy Institute, said that the shale revolution didn’t take off until the import terminal was “virtually complete.” Cheniere Energy, a company Smith calls a “trend setter,” was the first LNG import terminal that “immediately” converted to exporting. Cheniere put in the first application to the Department of Energy in 2010 for exporting approval and quickly received it.

The companies realized with more domestic production and low U.S. natural gas prices, they didn’t need the import terminals they had built, but they could use the docks and other facilities for exporting. “We can write it off or we can double our bet or triple our bet,” Smith said of the LNG industry thinking. “That’s what people did.”

Nikos Tsafos, senior fellow for the Energy & National Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, told us it takes about four to five years to build one of these exporting facilities. (Smith estimated six years.) “Everything coming on line now,” Tsafos said, was “authorized, approved and started construction during the Obama administration. You just can’t build these things much faster.”

Companies need essentially three approvals, Tsafos said. One from the Department of Energy to export to countries with which the U.S. has free-trade agreements, another to export to other nations, and a third on environmental and construction factors from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Sempra received the DOE approvals for its Cameron LNG project in January 2012 and September 2014, and the FERC approval in June 2014.

According to the Energy Information Administration, there are four LNG exporting projects in operation as of the first quarter of 2019, and two more are in the “commissioning” stage, which means they are beginning to produce LNG and get the equipment down to the proper temperatures. All of those received DOE and FERC approvals during the Obama administration.

Has the Trump administration instituted any policies that have affected LNG exporting? Tsafos said, “No.” He said the administration has a broad deregulation agenda, but “I would be very skeptical” that it has had a specific impact on LNG exporting. The Obama administration set up the approval system, “and that’s a system we still use.”

Smith responded, “yes,” but “in a negative sense” — citing the ongoing tariff battle with China. Liquefied natural gas is a major export to China, he said, and the last time China added tariffs in response to the U.S. increasing tariffs on Chinese goods (in the summer of 2018), the number of vessels exporting LNG dropped significantly. Reuters reported, citing shipping data, that only two vessels went from the U.S. to China in the first four months of 2019, compared with 14 in the first four months of 2018.

Even the potential of China increasing tariffs again on June 1 has an impact on the financing of these LNG projects, Smith said. China said on May 13 it would raise its 10 percent tariff on U.S. LNG to 25 percent. Companies need those 20-year contracts, such as Sempra’s with the Japanese conglomerates, so they’re assured of a market. “No bank is going to lend you money,” Smith said, if they’re not confident they will be paid back.

Smith said Trump may have been trying to highlight the fact that he has “encouraged shale gas production.” The president, he said, “has a tendency to shorten things up and make them sound more simple than they really are.”

LNG Exporting Wasn’t ‘Heading South’

Some LNG has been exported from Alaska for decades, but once these projects in the Lower 48 began operations, the amount of LNG exports has increased significantly. Cheniere Energy opened the first LNG exporting operation in the Lower 48 at its Sabine Pass terminal in 2016 in Louisiana. In 2017, it expanded its operations, and in early 2018, the Cove Point LNG project began operations in Maryland, according to the Energy Information Administration.

Trump falsely claims that LNG exports were “heading south” before he took office.

--

Trump, May 14: In the past two years, we’ve expanded our LNG exports to the world by nearly 500 percent. Five hundred percent. And it was heading south, folks. It was heading south, fast.

--

In fact, the large increase is due to projects approved before Trump took office, and the amount of exports increased by an even higher percentage in Obama’s last year.

In 2015, before these operations came on line, the U.S. exported 28.4 billion cubic feet of liquefied natural gas. In 2016, due to the launch of the Sabine Pass operation, that amount increased to 186.8 billion cubic feet. That’s a whopping 558 percent increase. From 2016 to 2018, exports went up 479.7 percent. But these percentage increases are nearly meaningless when the starting points are relatively low.

The EIA expects LNG export capacity to more than double by the end of this year, due to more projects beginning operations in 2019. This would give the U.S. the third largest export capacity in the world, after Australia and Qatar.

Energy Exports and Trade Deficits

Trump also said, “In 2018, American energy exports alone brought down our trade deficit by $215 billion.” That’s wrong.

Trump would be correct to say that without the nearly $188 billion (not $215 billion) in energy exports last year the total U.S. trade deficit would have been that much greater. But he’s wrong to say that exports “brought down” the overall trade deficit in goods and services, which actually went up in 2018 — by nearly $70 billion, or 13 percent, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Furthermore, the U.S. still runs a net trade deficit in energy. Energy imports exceeded exports by nearly $45 billion last year, according to the EIA. The energy trade deficit last year amounted to 7 percent of the total $622 billion trade deficit (see Table 1).

The White House did not respond to our questions, so we don’t know where Trump obtained his figure of $215 billion or why he said energy exports last year “brought down our trade deficit.”

Tsafos, at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, has written about America’s rising energy exports and the impact on the overall trade deficit. He referred us to the BEA for overall trade data and the EIA for energy trade figures.

In 2018, the U.S. imported $232.5 billion worth of energy and exported $187.6 billion for an energy trade deficit of $45 billion, the lowest it has been since 1985. The deficit peaked in 2008 at $415 billion, dropping by a staggering 89 percent since then, the EIA data show.

"The energy deficit used to be big — and, often, a big part of the overall trade deficit in goods — but that’s less true these days because the energy deficit has shrunk considerably, though, as you point out, it’s still a deficit,” Tsafos told us.

The rise in energy exports began in the early 2010s, driven by an increase in “onshore oil and natural gas production, aided by horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing technologies,” the EIA has said.

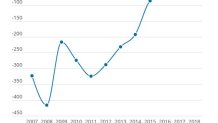

The energy trade deficit fell 85 percent under Obama, from $415.8 billion in 2008 to $61 billion in 2016, and it has declined 26 percent, so far, under Trump. (The chart below illustrates the 10-year trend.)

But, as the energy trade deficit has dwindled, the overall trade deficit in goods and services has continued to rise. Last year was the sixth straight year that the overall trade deficit in goods and services increased, rising from $552.3 billion in 2017 to $622.1 billion in 2018 — a jump of nearly 13 percent.

In a column last year, Tsafos wrote, “Energy has long played a major role in America’s trade deficits. Today, energy is seen differently: as a commodity to be exported, one that can help narrow trade deficits. Yet the hope that energy alone can solve this macroeconomic headache is misplaced. For one, over the last decade the non-energy trade deficit in goods has widened sharply even as the energy trade deficit has disappeared; energy can only do so much without the rest of the economy following.”