The following content is created in partnership with The National A. Philip Randolph Museum. It does not reflect the work or opinions of NBC Washington's editorial staff. Click here to learn more about The National A. Philip Randolph Museum.

A museum founded to recognize African Americans’ contribution to the nation’s labor movement is finding revived relevance as America’s unions face new opposition.

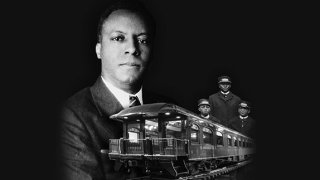

The National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum, is located in the Pullman National Monument, in Chicago, Illinois. Founded in February of 1995 it is the first, and currently, the only Museum in the country dedicated exclusively to African-American labor history, beginning with the African American Railroad workers. The museum honors and promotes the legacy of the Pullman Porters and A. Philip Randolph, who, in 1925, organized porters, and founded the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters (BSCP)—a union representing railroad porters of the Pullman Car Company.

Feeling out of the loop? We'll catch you up on the Chicago news you need to know. Sign up for the weekly Chicago Catch-Up newsletter here.

The BSCP was the first black labor union in America chartered under the American Federation of labor and the first to sign a collective bargaining agreement with a major U.S. corporation. The BSCP also opened the doors for African Americans to organize labor, creating a vehicle that built the black middle class.

This Saturday, Feb. 22nd, The National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum, a black labor history museum, the only one of its kind, celebrates its 25th anniversary with The A. Philip Randolph “Gentle Warrior Awards Gala fundraiser. As we observe Black History Month, we look at how unions helped create the black middle class—and how these very unions are now under fire.

Below, our chat with Don Villar, a Museum board member and the secretary-treasurer of the Chicago Federation of Labor.

How did labor unions help elevate classes in America?

Roughly a hundred years ago, there was a lot of sudden growth in the labor movement. We were coming out of industrialization and factories and mines were in terrible condition and the working conditions were awful. And wages were low.

People wanted a voice in the workplace. They started organizing and they formed unions at these shops and in the factories; in these mines and warehouses. They were able to get better wages, improve their working conditions. Folks could graduate from high school without a degree and just go into the factory or get into an apprenticeship program or just find other jobs.

At one time, union membership in this country was at one of three working people. Because of that, wages were good—the workers started building the middle class during the 40s, 50s, and 60s.

And how did unions help elevate African Americans in particular?

For African Americans, it was the Porters of BSCP who distributed the Black newspapers that contained information about employment opportunities in the north. It was an opportunity to leave the south and build a better life for themselves and their families—the Great Migration. Many came up to work at the mills and the stockyard here in Chicago. In the early part of the 1900s, they started to organize—and that built a lot of their communities, neighborhoods around the city. The BSCP, the Pullman Porters first chartered black union, helped to form communities. And they were making so much more money than those back in the towns they were from.

Today, in Chicago—especially within our public sector unions—we have a lot more black labor leaders than years ago. There’s our postal service, our teachers’ unions, the Services Employees International Union Healthcare. And then we also have a high black membership in these unions, like the CTA.

And when did labor

unions in this country start hurting?

You've seen a steady decline since the 70s. A lot of it’s political. It started

with Ronald Reagan firing all the striking members of air traffic control. In

the past there was always collaboration between government, labor and business.

But when he fired the workers, all of a sudden, the government took a side in

the fight. And that sort of signaled that process.

The laws defining workers in this country hasn't changed much since 1930. These laws were written for more of an industrial time. So right now, unions are hemmed in to represent the typical workplace—the boss and all the other workers below.

But now the workplace is so much different. You've got this whole disruption in the gig economy. Today, one of three workers is a contingent worker: They're part-time; they’re temp; they're freelancers; they’re independent contractors; they're self-employed. Because of this, they can't be organized. That's why there's a fight right now to try to treat them as full-time workers.

The National Labor Relations Board is very much the labor law in this country; they're the ones who decide oftentimes whether there’s a labor violation or not. Under eight years of President Obama, the labor board actually became more favorable towards workers. With contingent workers, the board was starting to break through, saying, hey, they may technically be on payroll through someone else, but they work under your direction. You tell them what to do.

Since President Trump took office, one of the things he did was replace leadership at the National Labor Relations Board and they started moving in the opposite direction. Also, President Trump and the Senate have appointed a lot of federal judges—they'll be handling a lot of employment law cases down the road, including labor law cases. I practice civil rights law. And if you have more of these judges who are more pro-corporate, they're going to decide against a lot of workplace issues in favor of companies. It will be much, much more difficult for worker plaintiffs to win.

How does this affect

the African American community in particular?

The overall decline in union membership tracks with the decline of the middle

class. There are so many graphs and research that point to that. You know, 12

percent of households in the state of Illinois are below the poverty level. And

there's another 24 percent who are employed, but they're the working

poor—they're one paycheck away from disaster.

Fortunately, here in Chicago, for the most part, the labor movement is strong. But in other parts of the country, yeah, it's been battered.

As organized labor struggles in most of America today, what kind of inspiration can people find at the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum?

The importance of unity, and the difference it can make. While modest in size, the museum is abundant with inspiration. George Pullman [head of the Pullman Car Company] had brought in Asian, Filipino, and Hispanic workers to try to break the union. He tried to create a wedge between young blacks, Asians, and Mexicans. And one of the great things about A. Philip Randolph: Instead of saying, They're the enemy—get mad and fight, he embraced them. And those folks also wised up. They realized they we're being used as a tool by George Pullman. And so, they turned around and became members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. As our founder, Dr. Lyn Hughes, says, “When people leave the museum, we think they are better versions of themselves. That is what our story does: It brings out the best in people."

For more information on The National A. Philip Randolph Museum—and to buy tickets for its 25th anniversary celebration—visit the museum site.