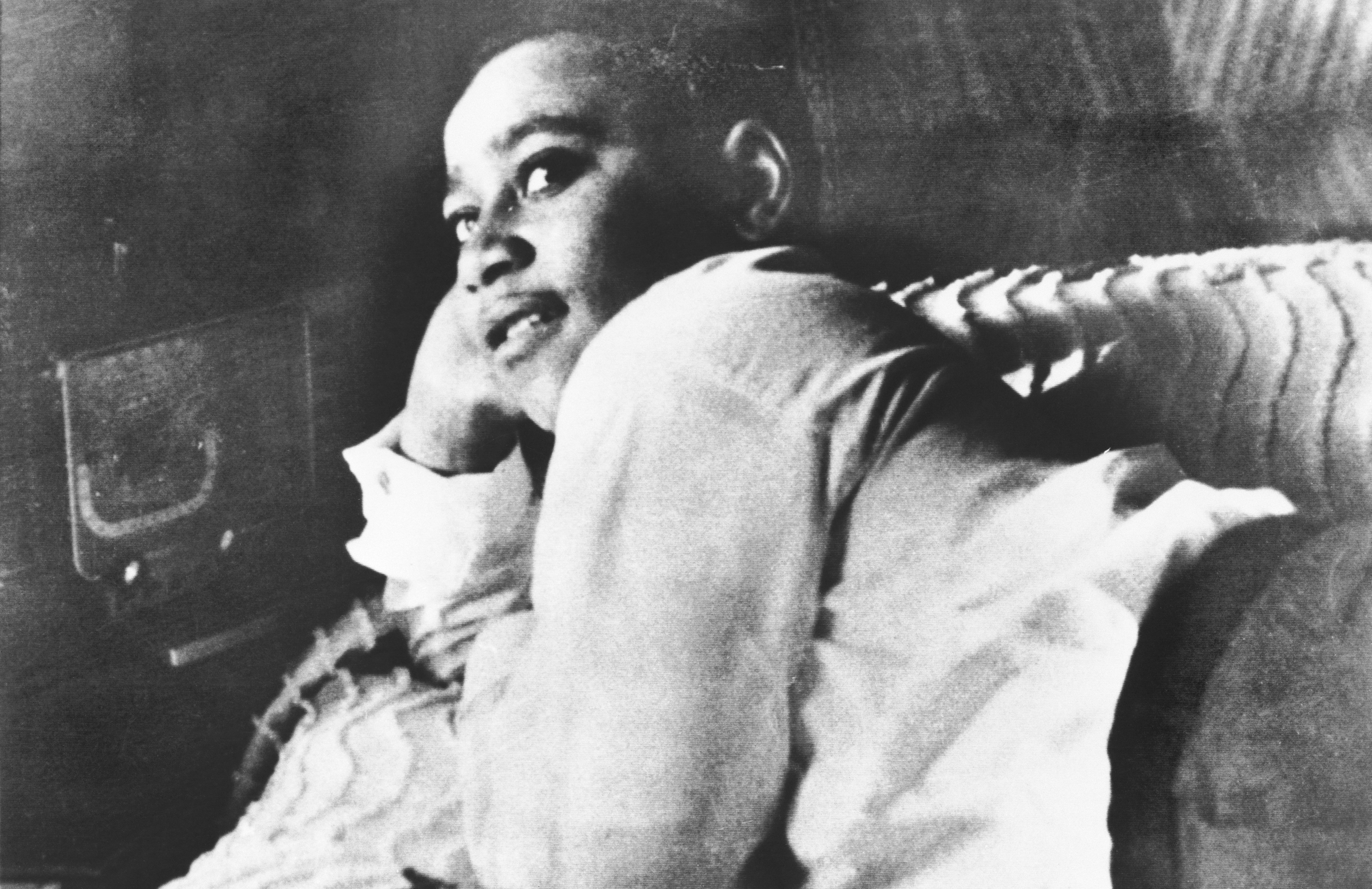

In an exclusive interview with NBC Chicago, new information about what led to the verdict in the decades-old murder of Emmett Till, a Black teenager from Chicago, may change what the world knows about the acquittal of two white men that marked a pivotal moment in American history.

Till’s death in 1955 sparked the modern-day Civil Rights Movement, his face no longer forgotten, along with the words, courage and tenacity of his mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, who did not rest in her pursuit of justice for her son.

At age 14, Till left his West Woodlawn home in Chicago and on Aug. 20, 1955, boarded a train to visit his extended family in Money, Mississippi, never to return home. He was murdered by two white men, Roy Bryant and Bryant’s half-brother J.W. Milam, after Till whistled at Bryant’s wife Carolyn, a white woman.

Bryant and Milam were eventually arrested, charged and tried for Till’s murder.

The trial made national headlines at the time, especially after the jury of all-white men acquitted Bryant and Milam despite days of dramatic testimony from witnesses who saw Till with his killers in the final hours of his life. One witness even testified to hearing Till’s screams from a barn run by the brother of the accused.

The testimony and evidence presented was not enough, and both men were found “not guilty” of Till’s murder.

Months after their acquittal, both Bryant and Milam confessed to the murder in a magazine interview in 1956.

Decades after the trial, the world has always thought the jury had reached a quick “not guilty” decision, based on deliberations reportedly lasting less than an hour, and by the added boasting of some jury members, who told the press at the time, "If we hadn’t stopped to drink pop, it wouldn’t have taken that long."

But according to new details, the jury’s initial vote was not unanimous.

In fact, three members of the jury required convincing by other jurors after first voting to convict Till’s killers, according to Stephen Whitaker, Ph.D., one of the first people to extensively research Till’s murder and the trial that followed.

In an exclusive interview with NBC Chicago, his first-ever television interview, Whitaker also said he discovered ways that the murder trial may have been fixed from the start, including one of the suspects’ defense attorneys, John Whitten, in his role as the county attorney for Tallahatchie, hand-picking the jury pool to ensure each person was “racist” and willing to set the white men free.

There were other forces influencing the trial, Whitaker learned, including key witnesses who were kept from testifying and hidden from view by the local Tallahatchie Sheriff at that time, H.C. Strider.

Whitaker discovered these facts about the witnesses who were shielded from view from his own stepfather, N.Z. Trout, who was the head of security for the Till trial and a deputy under Sheriff Strider.

Whitaker explained these new revelations in NBC Chicago’s latest documentary, “The Lost Story of Emmett Till: Then And Now,” now available to stream and watch here.

The documentary is the third chapter of an NBC Chicago series examining how Till’s story started a movement, the forces at play that tried to suppress his memory from the public conscience, as well as the corruption of the Mississippi justice system in 1955, the justice system that Till’s legacy and his family were thrown into.

“The verdict was unjust,” Till’s cousin Simeon Wright recalled. “But because of that verdict, Emmett Till’s memory and legacy is still alive.”

[Jurors] felt very bad about what they had done.

Stephen Whitaker, Ph.D. - Author, "A Case Study of Southern Justice: The Emmett Till Case"

Whitaker conducted the first extensive investigation of Till’s murder and the trial that followed for his Florida State University master’s thesis in 1963, titled “A Case Study in Southern Justice: The Emmett Till Case.” The thesis was chosen as the “best dissertation in the country” by The American Political Science Association, Whitaker said.

A Tallahatchie native, Whitaker knew the case intimately, as his stepfather was the head of security for the trial and was familiar with all the players involved.

“All the lawyers, both sides, the judge, [they] all gave me interviews,” Whitaker told NBC Chicago. “Everyone treated me well. Everyone was very open about it.”

Whitaker spoke with everyone connected to the Till murder investigation and trial, he told NBC Chicago, including nine members of the jury and one alternate.

That’s when he said he learned that the jury’s decision was not initially unanimous, as well as several more revelations about how the trial was influenced and manufactured to ensure Till’s killers walked free.

Whitaker chose not to include these facts in his master’s thesis, but he revealed them during an interview on the case with NBC Chicago.

In his research, Whitaker found when the all-white jury was seated for the trial, one of Bryant and Milam’s defense attorneys, John Whitten, had already handpicked every person in the jury pool, looking for a distinct quality.

"[Whitten] assured that the list from which the jury was taken only had people he was pretty certain were totally racist," Whitaker said. “And who would think nothing of killing an African American.”

Prosecutors knew it would be difficult to get a conviction of the white men.

The Tallahatchie County District Attorney Gerald Chatham requested help from the state to take on the case, and a former FBI Agent named Robert Smith III was appointed as special prosecutor.

Smith and Chatham had many challenges, but the handpicked jury pool they may not have known about.

Still, the prosecutors were aware that they were not getting any help from their own investigator: Tallahatchie County Sheriff H.C. Strider, a staunch segregationist.

Strider would end up testifying in Bryant and Milam’s defense.

This, despite the sheriff having a role in running things in the courtroom. Even there, Strider demanded segregation, including among members of the press.

Despite his interference, not only were white journalists interacting with Black journalists, they were also all working together to help further investigate the case—along with the NAACP and the Leflore County Sheriff George Smith.

Journalists were credited for finding some of the key witnesses who testified during the trial.

But other witnesses who could have made a difference were not present to speak, Whitaker’s research revealed, and he said that was Sheriff Strider’s intention.

Specifically, two men who were rumored to have accompanied Bryant and Milam during Till’s kidnapping: Levi “Too Tight” Collins and another man, not identified by federal investigators in the decades that followed the trial.

At the time of the trial, Special Prosecutor Smith remarked that his team was trying to identify and locate additional witnesses, in order to have them sworn in and testify.

“We’ve used every resource we know for days and days to bring them here, but they are just not here,” Smith told television reporters in 1955.

One of the witnesses that took the stand, an 18-year-old named Willie Reed, said he saw Collins during the kidnapping, as well as the other man, but they weren’t located to testify.

Whitaker revealed that’s because Sheriff Strider had moved Collins and the other man to a jail in Charleston, Mississippi, during the trial.

A report released in 2006 by the Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) specifies that Special Prosecutor Smith worked with Sheriff Strider and his deputy to try and find the witnesses in that jail, but the search came up empty.

In researching his thesis, Whitaker discovered the truth from his stepfather and the head of security for the Till trial, N.Z. Trout.

Whitaker said the men were in the jail, just under different names.

“He [Trout] confirmed it to me, many times,” Whitaker said. “My stepfather knew [that] they were in the jail. They were in the jail under assumed names so they could not testify, and they couldn’t be forced to testify or allowed to testify.”

After closing arguments in the murder trial concluded, and deliberations started, Whitaker said he found out, “The jury voted nine to three to acquit. There were three people on the jury that voted guilty.”

The second vote by the jury was also not unanimous, he found.

“On the second time, they voted 11 to one,” Whittaker said. He identified the last holdout as jury member Bishop G. Mathews.

But it wasn’t enough. The jury’s third and final vote was 12 to zero, Whitaker said. He learned that Matthews was the last holdout from the man's son, later in life.

Whitaker said these details on the jury’s votes have never been reported before, likely because members of the jury had come to an agreement among themselves, before Bryant and Milam’s acquittal was announced.

“[The jury] had an agreement among themselves not to- not to tell who voted,” Whitaker recalled. “But I know the one person who held out on the third ballot was Mr. Matthews.”

Despite the hubris of the “pop break” comment by jury members after the verdict was read, Whitaker said there was regret over finding Bryant and Milam innocent among the jurors.

“[They] told me later on that they felt very bad about what they had done,” Whitaker told NBC 5.